"To Emulate the British Stage": The Research and Design of the Douglass Theatre, Block 8

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1763

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2015

"To Emulate the British Stage":

The Research and Design of the Douglass Theatre

Block 8

Williamsburg, Virginia

Table of Contents

| 1. Précis | 1 |

| 2. Introduction | 3 |

| Theater Research in Williamsburg, 1947-1955 | 6 |

| 3. Research | 11 |

| The Nature of the Evidence | 11 |

| Weighing the Evidence: Design Assumptions | 20 |

| History of the Douglass Theatre, 1760-1775 | 22 |

| The Archaeological Evidence | 26 |

| 4. Design | 31 |

| The Scale of the Theater | 31 |

| Ancillary Rooms | 31 |

| The Framing and Exterior Materials | 32 |

| The Interior | 36 |

| Circulation | 38 |

| Auditorium Seating and Decoration | 40 |

| Orchestra Pit | 44 |

| Lighting | 46 |

| Ceiling and Ventilator | 47 |

| Stage | 48 |

| 5. Conclusion | 57 |

| 6. Endnotes | 59 |

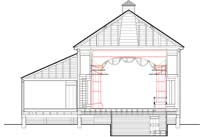

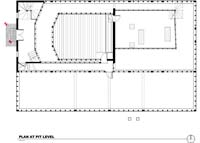

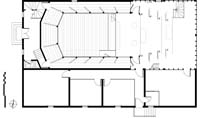

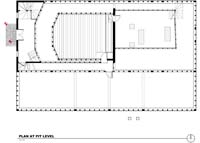

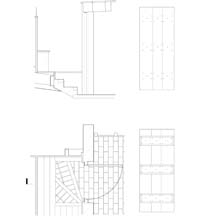

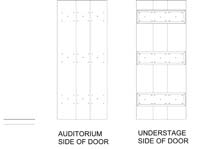

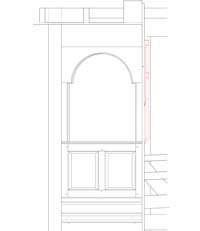

| 7. Portfolio of Design Drawings | 66 |

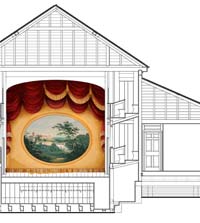

| 8. Portfolio of Digital Images | 107 |

Précis

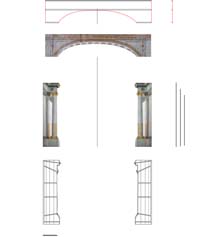

This report presents an overview of the research and design of the Douglass Theatre, a structure erected in Williamsburg in 1760 by the manager of the American Company of Comedians, David Douglass. Members of the Architectural Research Department under the direction of the now retired Vice President of Research, Dr. Cary Carson, worked on this project from 2003-2007. Dr. Carl Lounsbury was the principal researcher and Willie Graham was responsible for research and the design drawings. Carson and Edward Chappell helped with some of the fieldwork. Their work followed the excavation of the Douglass Theatre site by the Department of Archaeological Research. They benefited immeasurably from the periodic consultation with two prominent theater historians, Dr. Odai Johnson of the University of Washington, who has studied David Douglass' career, and Dr. David Wilmore, an English historian of eighteenth-century theaters, who had been involved in the most recent restoration of the Georgian Theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire. They also drew upon the expertise of a number of other scholars, especially Peter Perina, Pavel Slavko, Frank Hildy, and Iain Mackintosh, to vet the design of the Williamsburg theater at various stages in the project.

The third and last colonial theater in Williamsburg, the two-story Douglass Theatre stood in a prominent position on a lot just southeast of the second Capitol and was a popular gathering place in the evenings for legislators, government officials, and others during public times when the General Court and House of Burgesses adjourned for the day. For more than a dozen years, a full repertoire performed by Douglass' company of English actors entranced audiences that included habitual attendees George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. The Revolution disrupted Douglass's tour routine and the theater was eventually pulled down and some of its salvaged materials sold off in 1786. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries a number of buildings occupied the site of the Douglass Theatre and over time memory of its location eventually disappeared.

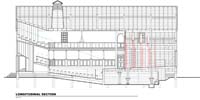

Working from fragmentary documentary evidence, the Department of Archaeological Research began excavating the site in the late 1990s and, after a number of seasons in the field, eventually discovered the footprint of the theater. Building upon the archaeological findings, Colonial Williamsburg's architectural historians developed the design of the theater based on precedents from standing English and European theaters and from documentary evidence associated with other theaters erected by Douglass in the American colonies, as well as material relating to English theaters found in a number of repositories. Once the design drawings were completed and reviewed by our American and European colleagues at a symposium held in Williamsburg in March 2007, Willie Graham worked with the Research Division's Digital History Center and with staff members from IATH (The Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities) at the University of Virginia to turn the paper drawings into a three-dimensional animated computer model replete with color, texture, and light, to recreate in the most captivating manner a sense of the intimacy of an eighteenth-century theater. This digital model was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation. Special thanks to Jonathan Owen for gathering images and laying out this report.

Introduction

"Haste, to Virginia's Plains, my Sons, repair

1

The Goddess said, Go, confident to find

An Audience Sensible, polit and kind

We heard and strait obey'd; from Britains Shore

These unknown Climes advent'ring to explore:"

David Douglass and the American Company

When David Douglass, the manager of an English company of actors whose circuit was the American colonies, arrived in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the late summer of 1760, he had few if any friends to welcome him. No doubt, he had gleaned some information of the place and its people from his wife, one of the leading actresses in the company. Before she became Douglass's spouse, she was the widow of another manager, Lewis Hallam, Sr., who had owned a theater in the city in the early 1750s. Earlier in her career, Mrs. Sarah Hallam Douglass would have met many of the principal figures of the town and, no doubt, relayed to her second husband the names of those residents well-disposed to the fortunes of the theater as well as describe the type of audiences who had filled her first husband's playhouse. Even more pertinent to his task at hand, the Scots-born manager came bearing letters of introduction from leading citizens and high officials in colonies to the north, which would open doors to the homes of the most influential men in the capital. The company had just completed a successful run in Annapolis and a favorable letter of recommendation from Maryland's Governor Horatio Sharpe to Governor Francis Fauquier probably gave Douglass access to the Governor's Palace and the influence that office had among the residents. Perhaps over a bowl of punch in one of the private rooms at the Raleigh or Wetherburn's Tavern or at the dining room table in one of the Randolph houses, he presented his case for the construction of a new theater.

As in provincial England, a theater in a colonial city spoke of the cultural aspirations of the place, where the stage brought the cultivated tastes and manners of the metropolis to audiences eager to keep abreast of the latest ideas and fashions.2 It was a mark of urbanity.3 In historian Odai Johnson's felicitous phrase, the theater was "London in a Box," a place for provincial Virginians to see the intricacies of contemporary taste and fashion on display. English actors demonstrated the "carriage, poise, dress, manners, [and] Augustan diction" of polite society in the British capital to an audience eager to emulate those genteel qualities.4 The playhouse engaged the mind and eye in a feast of words and rich spectacle. None played the medium better than Douglass (1720-1789).5 No quick-talking stroller of unknown pedigree and dubious business acumen, he stressed the propriety and

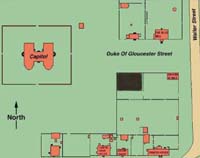

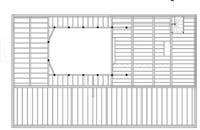

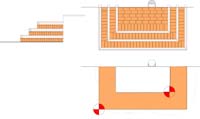

Fig. 1. Douglass Theatre site plan, Williamsburg, Virginia.

4

professionalism of his company, their legitimate connections with the London stage, and their successes in America. His beguiling words had already enabled him to build three theaters before he reached Williamsburg and would allow him to

continue to expand his circuit for another dozen years.6

Fig. 1. Douglass Theatre site plan, Williamsburg, Virginia.

4

professionalism of his company, their legitimate connections with the London stage, and their successes in America. His beguiling words had already enabled him to build three theaters before he reached Williamsburg and would allow him to

continue to expand his circuit for another dozen years.6

His credentials and appeal did not fail him in Williamsburg. With the charm of an actor reinforced by the Masonic handshake of a well-connected businessman, Douglass quickly persuaded crown officials, merchants, professionals, and planters of the necessity of building a theater in their capital.7 After getting official consent and securing a piece of property on which to erect the playhouse, he found a builder who would oversee its immediate construction. No doubt, Douglass banked on the loyalties and clout of his fraternal brothers to lend their weight in smoothing the necessary legal and financial transactions and in finding a willing member to undertake or oversee its construction at such short notice. Even with the help of his fellow Masons, he sought to broaden the appeal of a new theater because he needed others to share in the cost of building it. Perhaps through the provincial newspaper and by other means of communication, he solicited funds by setting up a public subscription whereby he would trade season tickets for a stake in the enterprise, an arrangement well known to American colonists and a practice that was typical of many English theater investments.8

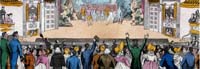

Within two months of his first appearance in Williamsburg, Douglass had added another venue to his growing American circuit. In October 1760, the American Company opened its first season in its new building prominently and purposely located a short distance from the Capitol. The haste to be up and running was governed by the schedule of provincial politics. The theatrical run was timed to coincide with the meeting of the provincial legislature and high courts, which ran from October 6th through October 20th.9 The political elite—the burgesses and council members who sat as the high court magistrates—as well as merchants, lawyers, and county officials from across the colony packed Williamsburg's taverns and guest houses for several weeks. Douglass anticipated rich pickings from a wealthy audience eager for an evening's entertainment after a day's labor at public business. He was not disappointed. Once members of Virginia's gentry including George Washington and others who had participated in the subscription scheme had settled into their box seats in the brightly lit auditorium, they found encouragement in the words of the opening prologue, were amused by the entr'acte, and were perhaps stirred by the spectacle of the main performance.10 At the end of the evening, they left the theater well assured that their enlightened patronage of the dramatic arts had been worth their investment. As Douglass had surmised, they would return for many nights to come.11 The American Company's success on the boards was matched by its members estimable behavior during their residency in Williamsburg, which did much to erase lingering doubts about the moral and financial probity of traveling actors stirred up by memories of an earlier troop.12

Fig. 2. Portrait of Nancy Hallam as Imogen disguised as Fidele in Shakespeare's Cymbeline. Charles Willson Peale,

artist, 1771. Hallam was a cousin of Lewis Hallam, Sr., who in 1752 had brought the first theater company from England

to the colonies.

Fig. 2. Portrait of Nancy Hallam as Imogen disguised as Fidele in Shakespeare's Cymbeline. Charles Willson Peale,

artist, 1771. Hallam was a cousin of Lewis Hallam, Sr., who in 1752 had brought the first theater company from England

to the colonies.

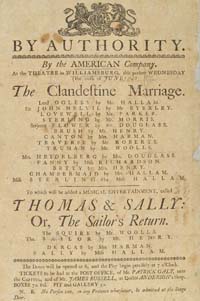

The American Company was organized in 5 the same manner and had a similar repertoire as many of the provincial companies that toured England in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, albeit the circuit extended from Newport, Rhode Island, in the north to Kingston, Jamaica, some 1,500 miles to the south. They generally timed their visits to coincide with the meeting of legislatures, courts, and other events that would draw larger audiences in smaller venues such as Annapolis and Williamsburg, or during the winter when they headed south to Charleston and Kingston.13 Between 1759 and 1763 David Douglass repeated the success he had in Williamsburg and managed to persuade local officials and backers to underwrite a series of playhouses in Newport, New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis, Charleston, and Kingston. He kept his company on the road and on the seas for nearly two decades before the War for American Independence disrupted the seasonal pattern of changing venues.14 In 1764-65, Douglass returned to London to hire actors, commission new scenery, and replenish his stock of plays. He was rewarded by packed houses and performed at a level unrivaled in colonial America. An English traveler who saw them in Annapolis in 1771 was surprised and delighted "on finding performers in this country equal at least to those who sustain the best of the first characters in your most celebrated [English] provincial theatres."15 Yet a handful of playbills, newspaper notices, and the memoirs of a few actors whose appearance on the American stage crossed or followed that of Douglass are nearly all that survive from the most successful of early professional theatrical companies.

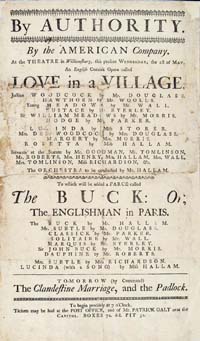

Fig. 3. May 1, 1771 playbill for Love In a Village and The Buck or The Englishman in Paris, performed by the American Company in Williamsburg, Virginia. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Fig. 3. May 1, 1771 playbill for Love In a Village and The Buck or The Englishman in Paris, performed by the American Company in Williamsburg, Virginia. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

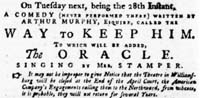

Fig. 4. Newspaper advertisement for the comedy The Way to Keep Him. The American Company planned to travel

northward on their circuit upon the close of the Williamsburg theater at the end of the General Court session. Virginia Gazette, eds. Purdie and Dixon, April 23, 1772, page 2.

Fig. 4. Newspaper advertisement for the comedy The Way to Keep Him. The American Company planned to travel

northward on their circuit upon the close of the Williamsburg theater at the end of the General Court session. Virginia Gazette, eds. Purdie and Dixon, April 23, 1772, page 2.

The tangible remains of this most ephemeral of eighteenth-century arts are the plays performed by the company and a few playbills and newspaper notices, which announced their repertoire and movement from place to place. Gone are the buildings in which they performed. None of the theaters constructed under Douglass's direction or the other playhouses where they acted in the late colonial period have survived. Most disappeared by the end of the eighteenth century. They were either converted to other uses, burned, or were torn down and replaced by larger and more imposing structures in the early republican era when theaters assumed the architectural forms and pretensions of public buildings. Contemporary 6 descriptions of Douglass's theaters are few and rarely detailed enough to envision with any degree confidence. However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the excavation of the Douglass Theatre site in Williamsburg revealed substantial information about its size and configuration. The archaeological record, combined with disparate documentary information about the building and those structures erected by the company in other American cities, provided the starting point for developing the design for its reconstruction. This paper presents an overview of the archaeological, documentary, and field research that informed the design for the reconstruction of the theater Douglass built on the edge of the Capitol square in Williamsburg in 1760.

Theater Research in Williamsburg,

1947-1955

Douglass's success in raising a theater in Williamsburg was not a unique act, for his was the third such structure in the colonial capital. Less than ten years earlier, another group of English players, the Murray-Kean company, had enticed the locals in 1751 to subscribe to the construction of a playhouse near the Capitol, somewhere in the vicinity of the reconstructed building known as Christiana Campbell's tavern on the eastern side of Waller Street. Alexander Finnie, the proprietor of the Raleigh Tavern, had arranged for the construction of the building that had also been paid for by subscription. Little is known about this building since its location and archaeological footprint has not been identified. Hard on the heels of the Murray-Kean Company, another itinerant troupe known as the London Company of Comedians led by Lewis Hallam, Sr. and his wife Sarah, late of the Goodman's Fields theater, played in Williamsburg in June 1752 in their inaugural tour of the American colonies. Hallam purchased the theater later that year and "with great Expense, entirely altered the Play-House … to a regular Theatre."16 The auditorium was divided into pit, box, and gallery seating and contained iron spikes lining the back of the orchestra pit.17 "The Scenes, Cloaths and Decorations," he announced to readers of Virginia Gazette, were "entirely new, extremely rich, and finished in the highest Taste, the Scenes being painted by the best Hands in London are excell'd by none in Beauty and Elegance." No pale, provincial production, Hallam assured the "Ladies and Gentlemen" of Williamsburg that they would be "entertain'd in as polite a manner as the Theatres in London."18 Hallam's company appeared at the theater intermittently over the next few years, but by 1757 the structure had been converted into a dwelling. David Douglass had absorbed a few of Hallam's players into his own company in the late 1750s after he married Hallam's widow. When he appeared in town soliciting subscriptions for a new theater in the late summer of 1760, he possessed a vicarious knowledge of the place and its leading citizens.

Fig. 5. First Theater, Palace Green archaeological site map, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Fig. 5. First Theater, Palace Green archaeological site map, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Theaters had been a part of Williamsburg since its infancy. In 1716, scarcely a decade and a half after the new capital had been laid out, merchant, dancing master, and entrepreneur William Levingston undertook the construction of "one good substentiall House commodious for acting such Plays as shall be thought fitt to be acted there." Levingston and his former servant Charles Stagg, who along with his wife Mary Stagg, agreed 7 to perform on the stage and teach their craft to aspiring actors, petitioned Governor Alexander Spotswood to obtain "a Patent or a Lycence … for ye sole Priviledge of acting Comedies, Drolls, or other Kind of Stage Plays within any part of ye sd Colony," which they were duly granted.19 Levingston's theater, the first purpose-built theater in America, was erected in the shadows of the Governor's house on a lot on the east side of Palace Street. Even though Levingston must have assumed Williamsburg to be a propitious place for such an undertaking, few documents point to a successful venture. Records are nearly mute as to its activities. In 1718 the governor sponsored a play in honor of King George's birthday, but there is little evidence that he followed up this success.

Fig. 6. First Theater, site foundations, Williamsburg, Virginia. Photographed 1931.

Fig. 6. First Theater, site foundations, Williamsburg, Virginia. Photographed 1931.

Despite operating a tavern in his dwelling next door and running a bowling green, Levingston could not sustain his thespian aspirations and mortgaged the property in the 1720s. Before the arrival of William Parks in the 1730s, there were no public printers in the town capable of producing the playbills or newspapers to advertise schedules. Perhaps even more detrimental to his efforts was the fact that no professional company made it their home over the thirty years it stood as a playhouse. Occasional strolling players hit the boards and students from the College of William and Mary used it in 1736 to perform such plays as Joseph Addison's Cato with its stirring political sentiments, but for the most part, Levingston's theater was underutilized through much of its history. In 1745 the two-story frame structure was converted into the city courthouse and served in such a capacity for the next quarter century before it was demolished.

Fig. 7. Levingston's Theater, plan of excavated foundations, Block 29, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Fig. 7. Levingston's Theater, plan of excavated foundations, Block 29, Williamsburg, Virginia.

In 1931 and again in 1947 the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation excavated the Palace Green site of the theater. The early work discovered many brick foundations on the three lots, but the interpretation was confused. The Colonial Williamsburg architects wrongly concluded that "the frame of the auditorium is assumed to be the frame of the central portion of the Tucker House." It was not, in fact, part of the theater, but the central part of Levingston's house, which had been moved in 1788 and formed the core of the St. George Tucker House.20 Realizing that more research would be necessary, fortunately, nothing was done about the reconstruction of the theater at the time. The 1947 excavations revealed the foundations of a building that was eighty-six feet in length and thirty feet wide. The shorter gable end of the theater faced the street and the long side ran the depth of the lot. Archaeologists also found two cross walls that were thought to define the area of the pit seating, the bottom of which did not sit in the ground but was raised slightly above it. Other than these walls, the excavators did not find any additional features that may have elucidated the arrangement of the various components of the building nor did they recover any artifacts that were specifically associated with the theater.21 Interest in the theater produced a flurry of reports by Colonial Williamsburg's research staff and others, which documented the history of the various companies and theatrical performances in the town in the 8 eighteenth century.22

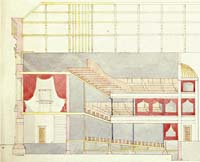

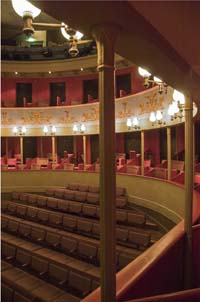

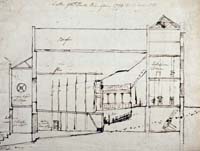

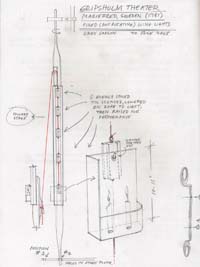

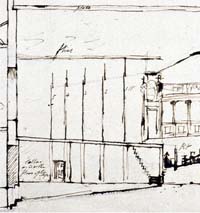

Although the archaeological remains of Levingston's theater were less detailed than they might have been (and the methods used to excavate the site in 1947 were far less informative than modern techniques), executives of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation asked its research historians and architects in 1948 to develop the design for the reconstruction of the first theater. In 1950 Singleton P. Moorehead, one of the foundation's restoration architects assigned to investigate eighteenth-century theaters, discovered the work of the noted English theater historian Richard Southern, who quickly became an integral part of the research that led to the design drawings for the first theater. Since the late 1930s, Southern had studied the fabric of surviving eighteenth and nineteenth-century English theaters, amassing in the process a large collection of theater images. His understanding of the architecture of the early English stage appeared in articles in the English journal The Theatric Notebook and led to the publication of The Georgian Playhouse in 1948 followed by Changeable Scenery in 1952.23 In 1951 Colonial Williamsburg architect Ernest Frank consulted with Southern in England where the two of them visited the 1788 Georgian Theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire, which was being examined by Southern in preparation for its restoration.24 They also looked at the 1766 Theatre Royal in Bristol, which still retained its original stage and some machinery (unfortunately destroyed in the early 1970s during a renovation). The following year Colonial Williamsburg architect Mario Campioli was in England to discuss the details of the Williamsburg theater design with Southern. On the advice of Southern, Campioli traveled to the continent to look at the royal theaters at Versailles and at Drottningholm.

Fig. 8. Georgian Theatre, 1788, Richmond, North Yorkshire, England. Photographed April 7, 2003 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

Fig. 8. Georgian Theatre, 1788, Richmond, North Yorkshire, England. Photographed April 7, 2003 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

Fig. 9. Theatre Royal, 1764-66, Bristol, England. Thomas Paty, architect, (c. 1713-89); unrestored gallery seats.

Photographed October 1, 2007 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

Fig. 9. Theatre Royal, 1764-66, Bristol, England. Thomas Paty, architect, (c. 1713-89); unrestored gallery seats.

Photographed October 1, 2007 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

The materials gathered by Frank, Campioli, and Moorehead from Williamsburg documents and the physical and documentary evidence from English theaters recorded by Southern informed the design drawings developed by Moorehead in his April, 1953 report "The Theatre of 1716 or the First Theatre in British America at Williamsburg, Virginia, A Report on its Proposed Design and Operation." The report outlined the few architectural precedents gleaned from the archaeological foundations and reveals the overwhelming reliance on Southern's knowledge of the English Georgian stage.25

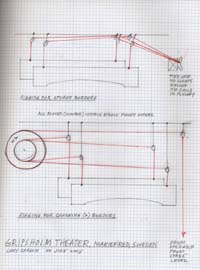

The culminating product of this collaboration was a one-half-inch scale model of the proposed reconstructed theater built under Southern's supervision in 1954. Elaborate in detail, filled with recognizable elements from various English playhouses, and animated with working 9 machinery such as sliding borders in grooved tracks, a retractable chariot, and a thunder machine based on the surviving one in the roof of the Bristol theater. Clusters of scale figures of actors and audience members in dramatic poses enlivened the Williamsburg model in a manner that had become characteristic of Southern's work. Southern's model is very similar in style to a number of English ones that he made including the Georgian Theatre in Richmond.

Fig. 10. Detail of the model of the first theater in Williamsburg, 1716, Palace Green. English theater historian Richard Southern created the model in 1953-54 for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Photographed March 13, 2007 by Jeffrey E. Klee.

Fig. 10. Detail of the model of the first theater in Williamsburg, 1716, Palace Green. English theater historian Richard Southern created the model in 1953-54 for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Photographed March 13, 2007 by Jeffrey E. Klee.

Although the framing and architectural details were largely based on Williamsburg and Chesapeake precedents, the plan of the auditorium closely replicated the Georgian Theatre in Richmond. The stage machinery, wings, and borders were fully the product of Southern's expertise. In hindsight, it is easy to see that the variety and types of complicated machinery that appeared in the model were anachronistic in many respects, being far more elaborate and technologically advanced than that used on even the best English stages at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

In 1955 after a review of changes that were required to make the Levingston theater acceptable for modern performances, audiences, and stringent fire regulations (reducing the number of occupants from over 600 to less than 300, for instance), the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation decided not to reconstruct the building. Moorehead's design drawings were shelved and Southern's model began a peripatetic life moving from one office to another within the foundation, finally coming to rest in the Architectural Research Department, where in recent years it has spawned new attention beyond its curiosity as a relic of earlier theater research. The investigation of David Douglass's 1760 theater and our discussions with contemporary English historians have revealed a growing appreciation of the seminal role that Richard Southern played in professionalizing the study of the English stage 10 both in the fields of theater design and performance in the decades following the Second World War.26 Richard Leacroft in England and Brooks McNamara in America inherited Southern's mantle in their explorations of eighteenth-century theater architecture.27

Fig. 11. Playbooth Theater, actors performing, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Fig. 11. Playbooth Theater, actors performing, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Had Colonial Williamsburg decided to reconstruct the Levingston theater sixty years ago based on the Moorehead-Southern design, the foundation would have built an anachronism, a building far more elaborate than the few theaters erected in provincial England in the early eighteenth century and certainly beyond the technological capabilities available in early Williamsburg. The details of their design, especially the extensive use of stage machinery and the complex circulation and seating patterns of the auditorium (with its double pit passages), are associated with English theaters of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, not the first decades of the 1700s.28 More pertinent to this study, a reconstructed Levingston theater would have precluded the archaeological search for the more prominent later theater and the architectural research that followed the excavation of the Douglass site.

Although the research and design of the late 1940s and early 1950s did not result in the construction on an eighteenth-century theater, the desire to stage theatrical performances in Williamsburg did not end. Over the next half century, a number of individuals continued to speak on behalf of the reconstruction of a theater. In many guises and with varying degrees of professionalism and fidelity to the eighteenth-century repertoire, companies of actors staged performances in modern settings, most notably in the auditorium of the Williamsburg Lodge, where audiences could experience some aspects of being in a colonial playhouse.29 In the late 1980s, a simply fashioned play booth was erected on the site of the first theater and small outdoor vignettes and snippets of plays were performed by a band of costumed interpreters who also recounted Williamsburg's theatrical history.30 These modest efforts to keep the memory of eighteenth-century theater before the public and Colonial Williamsburg officials led to the renewal of theater research in the 1990s. That research had the advantage of building on these earlier efforts.

Architectural Research

The Nature of the Evidence

The research evidence that guided the design of the Douglass Theatre derived from a variety of sources, which can be divided into two broad categories. The first is primary evidence relating to the Douglass Theatre itself and the individuals who acted on its stage or watched performances in the auditorium. The second category is analogous evidence associated with eighteenth and nineteenth-century theaters, buildings, and the English and American stage. Site specific information comes from evidence discovered through archaeological excavation of the Douglass Theatre site, first in 1940 and then again from 1996 through 2001. Archaeologists discovered the footprint of the building and a few artifacts associated with its construction and use.31

Fig. 12. Purported footlight for the first or second Williamsburg theater. It was discovered in the attic of the St.

George Tucker House in 1953. It is constructed of light wood or cardboard covered with hand made linen cloth, instead of

metal, suggesting a copy rather than an actual footlight.

Additional information appears in a variety of written sources that record the presence of Douglass and his company in Williamsburg from 1760 through the early 1770s. Documents pertaining to the theater range from surviving playbills and newspaper notices of performances, which not only shed light on the repertoire of the American Company, but described the type and price of seating in the auditorium and the fact that tickets had to be purchased at off-site locations, implying that there was no box office in the building. From

Fig. 12. Purported footlight for the first or second Williamsburg theater. It was discovered in the attic of the St.

George Tucker House in 1953. It is constructed of light wood or cardboard covered with hand made linen cloth, instead of

metal, suggesting a copy rather than an actual footlight.

Additional information appears in a variety of written sources that record the presence of Douglass and his company in Williamsburg from 1760 through the early 1770s. Documents pertaining to the theater range from surviving playbills and newspaper notices of performances, which not only shed light on the repertoire of the American Company, but described the type and price of seating in the auditorium and the fact that tickets had to be purchased at off-site locations, implying that there was no box office in the building. From

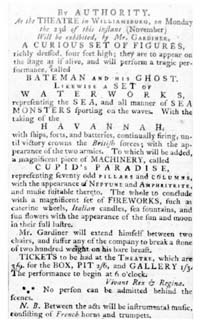

Fig. 13. Newspaper advertisement illustrating a variety of entertainments and the range of props, equipment and

machinery used on stage. Virginia Gazette, ed. Rind, November 19, 1772, page 3.

12

account books of Williamsburg merchants, diaries of spectators, and land records, small tidbits of information survive that document the purchase of vast quantities of candles to light the playhouse, note the accommodation of some of the company in taverns and boarding houses, and reveal the Masonic affiliation of Douglass and some of his actors.

Fig. 13. Newspaper advertisement illustrating a variety of entertainments and the range of props, equipment and

machinery used on stage. Virginia Gazette, ed. Rind, November 19, 1772, page 3.

12

account books of Williamsburg merchants, diaries of spectators, and land records, small tidbits of information survive that document the purchase of vast quantities of candles to light the playhouse, note the accommodation of some of the company in taverns and boarding houses, and reveal the Masonic affiliation of Douglass and some of his actors.

Because the theater stood for such a brief time—certainly no more than twenty years—these primary sources leave many questions unanswered. There are no detailed descriptions or drawings of the building. As with so many Williamsburg

projects, much of the design for the reconstruction had to be based on analogous evidence found in material not specifically related to the Douglass Theatre or even to Williamsburg. The size, entrance, and general configuration of the auditorium, stage, and ancillary spaces left their imprint in the ground, but how those soil stains translated into bricks, weatherboards, stage fittings, and decorative features cannot be directly interpreted from the physical or documentary evidence. As with many reconstructions, we have had to look further afield to other buildings. Obviously, we drew on the scant information about the dozen or so theaters Douglass built in the mainland colonies and the Caribbean in the 1760s and early 1770s, believing them to be the most pertinent to our structure in Williamsburg. Fortunately, there are tantalizing fragments of information about the buildings in New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis, Charleston,

Kingston, and other places, but none of them richly documented. There are useful references describing

the size of many of these theaters, the stage scenery,

Fig. 14. Portrait of James Winston, engraved 1805 by William Ridley, published by Vernor & Hood.

Fig. 14. Portrait of James Winston, engraved 1805 by William Ridley, published by Vernor & Hood.

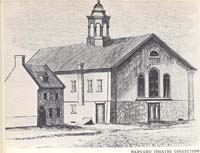

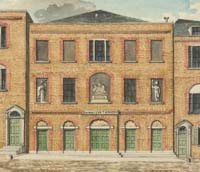

Fig. 15. Newark Theatre, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England; exterior, 1804. Watercolor painted by Daniel Havell; signed by J. D. Curtin; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook, HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 28, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 15. Newark Theatre, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England; exterior, 1804. Watercolor painted by Daniel Havell; signed by J. D. Curtin; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook, HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 28, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

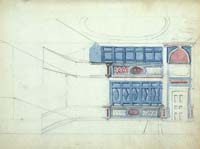

Fig. 16. Brighton Theatre, East Sussex, England; sketch of entrance facade; James Winston Collection, TS 1335.211, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 16. Brighton Theatre, East Sussex, England; sketch of entrance facade; James Winston Collection, TS 1335.211, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 17. Brighton Theatre, East Sussex, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook, HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 22, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

13

the kind of candles employed in lighting the house, and the presence of ancillary rooms.

Fig. 17. Brighton Theatre, East Sussex, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook, HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 22, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

13

the kind of candles employed in lighting the house, and the presence of ancillary rooms.

Fig. 18. Southwark Theatre, Philadelphia; reconstructed view. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 18. Southwark Theatre, Philadelphia; reconstructed view. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

These fragmentary sources cannot provide the detailed information needed for the reconstruction of the Douglass Theatre in Williamsburg. Therefore, we have had to draw upon information from further afield, using evidence found in a variety of prints, documents, and drawings of other American, English, and European theaters. Dozens of late eighteenth- and

early nineteenth-century English prints survive, most of which depict the stage and auditoriums of London's theaters. Though these theaters dwarfed the scale of Douglass's venue in Williamsburg as well as nearly every English provincial theater built in the mid-eighteenth century, the prints illustrate important details concerning lighting, box sizes,

Fig. 19. Newcastle Theatre, Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 14, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

14

pit seating, proscenium decorations, traps, and backdrops.

Fig. 19. Newcastle Theatre, Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 14, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

14

pit seating, proscenium decorations, traps, and backdrops.

Perhaps the most useful, and certainly the most voluminous source of information about British theater architecture is the material that was gathered in the early nineteenth century by James Winston, an actor who later managed theaters in London. Winston compiled information about the history and operation of contemporary theaters in Great Britain. In 1805, he began publishing brief histories of provincial theaters in several installments in a series he entitled The Theatric Tourist. Although two dozen towns appeared in print, he never finished a project that would have included as many as seventy to eighty other sites across Great Britain.32 His collection of notebooks, measured drawings, watercolors, and letters now lie scattered across several continents in many different archives after it was sold at auction in 1849, six years after his death.33 In his four volumes of notebooks in the Harvard Theater Collection, Winston scribbled stage anecdotes, descriptions, and estimates of nightly purses for more than 250 theaters spread across England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and America, though information on theaters in the new world is meager. However, he did manage to track down and transcribe the prologue spoken in Williamsburg in September, 1752 on the opening night of Lewis Hallam, Sr.'s London Company in the second theater (see Introduction).34

Fig. 20. Stroud Theatre, Gloucestershire, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston, Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 52, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 20. Stroud Theatre, Gloucestershire, England; exterior. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston, Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 52, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Ranging from detailed letters, summary descriptions of hundreds of provincial theaters, to dozens of scaled plans, sections, elevations, details, and watercolor sketches, the Winston material proved to be invaluable in answering specific questions about variations in sight lines in pits, boxes, and galleries, leg room and bench widths, circulation patterns, stage heights in relation to orchestra pits, forestage lengths, lighting, traps, machinery, decorations, and color. Winston's collection at the Houghton Library at Harvard, the Theatre Museum in London, the Folger Library in Washington, and other institutions also includes a rich variety of visual material ranging from sketches of columns and seating, scaled plans, elevations, and sections of specific theaters, to a series of commissioned watercolors (in several iterations) of more than seventy exterior views.

Fig. 21. Penzance Theatre, Union Hotel, Penzance, Cornwall, England; side elevation. Watercolor by Daniel

Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 10, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 21. Penzance Theatre, Union Hotel, Penzance, Cornwall, England; side elevation. Watercolor by Daniel

Havell; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 10, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In addition to contemporary correspondence (much of which he copied more than once into a series of notebooks), Winston also included information gleaned from published sources, including reminiscences of actors such as Tate Wilkinson and managers who had memories of the stage from the era that extended from David Garrick in the mid-eighteenth century to the first decade of the nineteenth century. For some cities and towns, Winston amassed several pages of 15 notes mostly concerning the history of a particular theater, its managers, players, length of the season, and amusing anecdotes.

The notebooks describe a few theaters in some detail, which occasionally included information regarding the arrangement of the auditorium, stage, ancillary rooms, lighting, finish, and seating capacity (calculated as the amount of money that could be made in an evening usually based on the charge of three shillings per box seat, two shillings for pit seat, and one shilling for gallery seat). Most entries, however, say little about architectural details, noting at best improvements

in house seating such as the installation of front boxes or new sets of scenery by a noted London scene painter. Since this compilation is a manager's view of the theater, missing are details concerning stage fittings, props, machinery, traps, and other features. References are occasionally made about the quality of the wardrobe, the presence of a green

room, and the location of dressing rooms. These often appear incidentally as amusing anecdotes such as the description

of a temporary theatrical venue in Macclesfield in a very leaky stable whose

Fig. 22. Windsor Theatre, Berkshire, England; exterior. Watercolor. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 34, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 22. Windsor Theatre, Berkshire, England; exterior. Watercolor. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 34, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 23. Theatre Royal, Plymouth, England; side boxes, Juliet box, and stage door. James Winston Collection; TS 1335.211, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 23. Theatre Royal, Plymouth, England; side boxes, Juliet box, and stage door. James Winston Collection; TS 1335.211, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

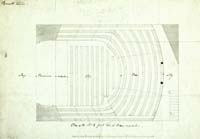

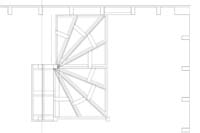

Fig. 24. Theatre Royal, Plymouth, England; improved plan showing auditorium, stage, proscenium, orchestra pit, pit, lower and side boxes, lobby, and stairs; drawn November 1803. Winston Collection; PFMS THR 344(19), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

16

stalls had been fitted up as dressing rooms.35

Fig. 24. Theatre Royal, Plymouth, England; improved plan showing auditorium, stage, proscenium, orchestra pit, pit, lower and side boxes, lobby, and stairs; drawn November 1803. Winston Collection; PFMS THR 344(19), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

16

stalls had been fitted up as dressing rooms.35

Fig. 25. Wells Theatre, Somerset, England; side elevation. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric

Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 33, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 25. Wells Theatre, Somerset, England; side elevation. Watercolor by Daniel Havell; James Winston Theatric

Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 33, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Winston commissioned several artists to sketch exterior views of approximately fifty to seventy buildings. The images generally depict a theatre within an urban streetscape. A few are drawn in isolation, but most show shops, dwellings,

and a few public buildings nestled against the theatre. Some drawings are skillfully composed; others are merely impressionistic in poorly rendered perspective. The degree of finish varies as well from pencil sketches to finished watercolors. The watercolors (sixty-eight of which are bound together at the Houghton Library at Harvard) served as the source for the engravings for views of the twenty-four theaters published in The Theatric Tourist.36 Most of these seventy watercolors are labeled or can be identified, but a few are not.37 Some sites were painted more than once and some

Fig. 26. Theatre Royal, Bristol England; second tier gallery seating. Red lines indicate original bench seat locations. Drawn September 30, 2007 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

Fig. 26. Theatre Royal, Bristol England; second tier gallery seating. Red lines indicate original bench seat locations. Drawn September 30, 2007 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

Fig. 27. Broadstairs Theatre, Kent, England; front facade; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol.

2, page 13, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 27. Broadstairs Theatre, Kent, England; front facade; James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol.

2, page 13, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 28. Rochester Theatre, Kent, England, exterior. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2

page 19, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

17

buildings have several versions of nearly identical views. There are duplicates in the Harvard collection. Copies and similar views are also found in a collection of Winston material in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, Australia.38 The final engravings for The Theatric Tourist were created from a series

of critiqued images that, at least in some cases, started as sketches found in the Harvard material. Winston would make comments on these and passed them along to the artist who painted them in watercolors, often reworking the scale of the

building and adding people and other details. The engraver then further embellished the image and adjusted the perspective. Thus not all details in these views can be trusted as entirely factual.

Fig. 28. Rochester Theatre, Kent, England, exterior. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2

page 19, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

17

buildings have several versions of nearly identical views. There are duplicates in the Harvard collection. Copies and similar views are also found in a collection of Winston material in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, Australia.38 The final engravings for The Theatric Tourist were created from a series

of critiqued images that, at least in some cases, started as sketches found in the Harvard material. Winston would make comments on these and passed them along to the artist who painted them in watercolors, often reworking the scale of the

building and adding people and other details. The engraver then further embellished the image and adjusted the perspective. Thus not all details in these views can be trusted as entirely factual.

Fig. 29. Detail of entrance facade with three exterior doors leading to the pit, box, and gallery seating, Broadstairs Theatre, England. Watercolor in the James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2., Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 29. Detail of entrance facade with three exterior doors leading to the pit, box, and gallery seating, Broadstairs Theatre, England. Watercolor in the James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2., Houghton Library, Harvard University.

These watercolors and the published images in The Theatric Tourist record English theater architecture during a time of great transition at the beginning of the nineteenth century. From very modest beginnings, theaters were developing into very self-conscious building types, prominently positioned on the High Street of many provincial towns. Some appear in fashionable neoclassical garb with recessed arches, delicate ironwork, elliptical fanlights, symmetrical architraves, attenuated columns, and thin window muntins (sometimes painted black). The royal coat of arms or those of a patron are prominently emblazoned on some buildings. Lamps hung from wall brackets illuminated their presence. Many of the newer theaters have multiple entrances to different parts of the auditorium. Doors labeled "box," "pit," and "gallery" directed patrons to their seats, suggesting that circulation patterns were becoming more complex and money to hire doormen more plentiful at the beginning of the nineteenth century. At Windsor, the Theatre Royal had three entrances to direct theater-goers to their proper places. The gilded coat of arms of the king hung above the central door and was flanked by those of the princes royal on one side and the Prince of Wales on the other over the secondary entrances.39

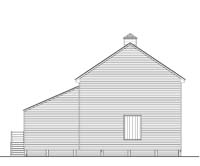

Yet at the same time, this transformation was far from complete. Interspersed among these architecturally stylish buildings are a number of edifices that reflect a much older and far humbler architectural pedigree. At Windsor, for example, a proper theater was late in coming. In the middle of the eighteenth century, theatrical entertainments

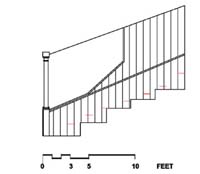

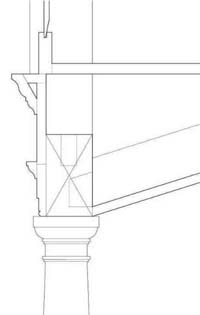

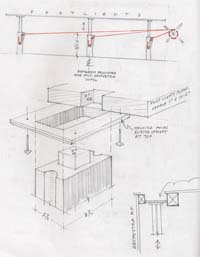

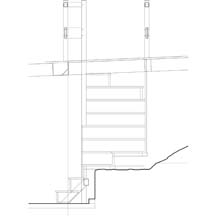

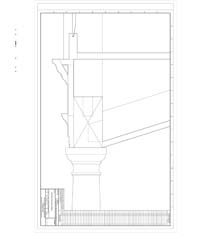

Fig. 30. Georgian Theatre, Richmond, North Yorkshire, England, 1788; trap framing. Field notes by Willie Graham, April 8, 2003.

18

Fig. 30. Georgian Theatre, Richmond, North Yorkshire, England, 1788; trap framing. Field notes by Willie Graham, April 8, 2003.

18

Fig. 31. Castle Theatre, Český Krumlov, Czech Republic; view of stage and orchestra pit during the performance of J. J. Fux's opera Giunone Placata. Photographed June 3, 2005 by Willie Graham.

were performed at a temporary booth. This was superseded in 1778 by a more permanent venue in a refitted barn "in a dirty farm yard" half a mile out of town, which, needless to say, never attracted royal visitors.40 In a bid to replace the old theater built in Colchester in 1764, the proprietors observed in 1810 that it was an inconvenient

structure "having but one access, and that thro one of the courts of the town-hall, & part of the jail & having no passages to the side or green Boxes above." What they wanted was a structure with a conspicuous and multi-entranced "Frontispiece" along with an interior filled with "Stage traps, Grooves, Machinery, Scenes, Wings, Lamps, Flats, Lustres, &c." since the old one was failing to attract large audiences.41

Fig. 31. Castle Theatre, Český Krumlov, Czech Republic; view of stage and orchestra pit during the performance of J. J. Fux's opera Giunone Placata. Photographed June 3, 2005 by Willie Graham.

were performed at a temporary booth. This was superseded in 1778 by a more permanent venue in a refitted barn "in a dirty farm yard" half a mile out of town, which, needless to say, never attracted royal visitors.40 In a bid to replace the old theater built in Colchester in 1764, the proprietors observed in 1810 that it was an inconvenient

structure "having but one access, and that thro one of the courts of the town-hall, & part of the jail & having no passages to the side or green Boxes above." What they wanted was a structure with a conspicuous and multi-entranced "Frontispiece" along with an interior filled with "Stage traps, Grooves, Machinery, Scenes, Wings, Lamps, Flats, Lustres, &c." since the old one was failing to attract large audiences.41

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, many English touring companies continued to perform in decidedly down-market venues such as stables, barns, converted dwellings, and taverns more redolent of the types of temporary and makeshift accommodations experienced by players in the early and mid-eighteenth century in England and America.42 Here and there the Winston drawings depict a ramshackled playhouse situated in the back street, back lot, or on the edge of town. Rather than multiple entrances, these buildings have ladders or wooden steps leading to a single entrance and timber-framed walls devoid of windows. Signs are few; lamps conspicuously absent. Except in the major provincial towns, these buildings with unassuming exteriors and undifferentiated entrances are the contemporaries of the Douglass Theatres erected in the American colonies in the 1760s. Pretentious facades, multiple entrances, and prominent locations seem to be products of the last few decades of the eighteenth century and opening years of the new one.

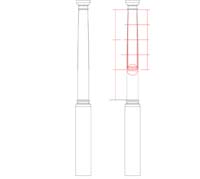

The Winston collection contains several drawings unrelated to the Theatric Tourist project. Many of these are scaled drawings depicting plans, elevation, sections, and details of individual theaters, some of which can be identified such as the ones for the remodeling of the theaters in Plymouth and Birmingham. They range from grand structures to small provincial ones far smaller than the Douglass Theatre in Williamsburg. The material even contains two detailed drawings of stage sets and costumes.

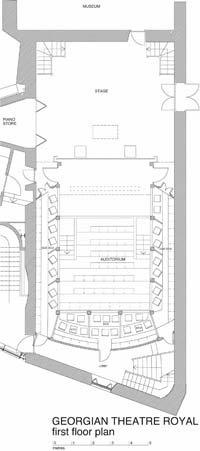

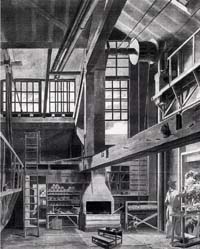

In the absence of standing early American

19

Fig. 32. Castle Theatre, 1766, Český Krumlov, Czech Republic; orchestra pit music stand detail. The stand is communal and is lit by candles set in glass cups that are attached by a metal (possibly iron) ring to the stand. Two benches allow the musicians to play on both sides of the stand. Photographed June 7, 2005 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

theaters, we turned to surviving English and European structures for both detailed and more general information about their arrangement of seating and circulation patterns to the methods used in the construction of stage scenery, thunder

machines, and lighting devices. Among the many British and European theaters we visited, the most important were the Georgian Theatre (1788) in Richmond, North Yorkshire, the Theatre Royal (1766) in Bristol, the stable theater in Penzance,

the Theatre Royal in Bungay, the Castle Theater in Český Krumlov (1766) in the Czech Republic, and the Slottsteater (1766) in Drottningholm, Sweden.

Fig. 32. Castle Theatre, 1766, Český Krumlov, Czech Republic; orchestra pit music stand detail. The stand is communal and is lit by candles set in glass cups that are attached by a metal (possibly iron) ring to the stand. Two benches allow the musicians to play on both sides of the stand. Photographed June 7, 2005 by Carl R. Lounsbury.

theaters, we turned to surviving English and European structures for both detailed and more general information about their arrangement of seating and circulation patterns to the methods used in the construction of stage scenery, thunder

machines, and lighting devices. Among the many British and European theaters we visited, the most important were the Georgian Theatre (1788) in Richmond, North Yorkshire, the Theatre Royal (1766) in Bristol, the stable theater in Penzance,

the Theatre Royal in Bungay, the Castle Theater in Český Krumlov (1766) in the Czech Republic, and the Slottsteater (1766) in Drottningholm, Sweden.

A great variety and some very detailed information came from this field evidence. We found ghost marks that revealed the width and the rake of box and gallery seating in the Theatre Royal in Bristol, recorded the size and construction of the traps in the stage floor in the Georgian Theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire, and recovered evidence of the arrangement of the orchestra pit in an early nineteenth-century theater in Bungay. Paint samples revealed early decorative schemes and finishes of boxes and auditorium walls in Bristol and Richmond.

The theaters in Český Krumlov and Drottningholm have well preserved stage machinery, scenery, and lighting devices among many other features that rarely survive in British theaters or elsewhere and we drew heavily upon the details we found in these buildings regarding the fabrication of stage scenery and its framing and props. However, we knew that these European precedents were foreign in many ways to the traditions of the English stage that David Douglass and his performers knew so well. We carefully compared the field evidence from sources outside the common experience of English actors against 20 what we had gathered from documentary material more closely associated with the English stage. In some cases, such as the attachment of the painted canvass scenery used in the borders, we had only the evidence from the Czech Republic and Sweden to draw upon.

Weighing the Evidence: Design Assumptions

The decisions made governing the design of the Douglass Theatre were based on assumptions about the value of the disparate evidence that was gathered. Some site specific evidence established basic parameters, most clearly the archaeological footprint which defined the orientation, size, and general arrangement of the building. But what did the auditorium, stage, backstage, and ancillary rooms look like? How did they function? How were they finished? How were they furnished? Could we assume a certain amount of similarity among the theaters built by Douglass during the period when he was establishing his American circuit? Could various types of evidence from English theaters be taken as typical of the period or should they be seen as unique survivors, perhaps not at all reflective of eighteenth-century theaters? How much stock should we put into a piece of evidence found in an English drawing or in an artifact found in a Czech castle theater?

Fig. 33. Theatre Royal, 1768, plan, Edinburgh, Scotland. Edinburgh Reference Library. Published in David Thomas, ed., Restoration and Georgian England, 1660-1788 (Theatre in Europe: A Documentary History), New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989; page 297.

Fig. 33. Theatre Royal, 1768, plan, Edinburgh, Scotland. Edinburgh Reference Library. Published in David Thomas, ed., Restoration and Georgian England, 1660-1788 (Theatre in Europe: A Documentary History), New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989; page 297.

We developed the design for the reconstruction of the Douglass Theatre working with the following assumptions about the construction of the original building in 1760:

- 1.

The shell of the building would have been erected by Williamsburg craftsmen, not by outsiders or theater specialists. The building would have been constructed and finished in a manner consonant with local building practices. Brickwork, framing methods, doors and paneling, stairways, and decorative details of the more general nature would have been based on typical features found in other late colonial buildings in Williamsburg and the surrounding region.

Williamsburg carpenters were well versed in the language of theater construction, having already built two before Douglass' arrival. Douglass would have been able to further enlighten the craftsmen on nuances of theater design based on his experience of building other theaters in America as well as his observation of English ones.

- 2.The form and arrangement of the stage, auditorium, and ancillary rooms, their decorative treatment, and circulation patterns are based on the archaeological record as well as evidence from Douglass's other American theaters and contemporary English ones as found in standing structures and documentary material.

- 3.Specialized theater details including lighting, scenery, props, machinery, and certain decorative details associated with the theater would have been based on English and European examples and any documentary evidence from Douglass's theaters or other early American theaters. Douglass turned to specialists in London for many of these items.

- 21

- 4.The Douglass Theatre was a proper provincial English theater consonant with the scale and level of finish found in the better houses in the English provinces. It was not a makeshift venue or a naïve colonial version of contemporary forms.

Our study of the Winston material has convinced us that the Williamsburg theater was built on a scale and in such a fashion as the better class of provincial English theaters in which there were certain expectations of architectural refinement. Eighteenth-century theater managers thought of their buildings in terms of the number seats and types of tickets that could be sold for an evening's performance. Based on a hierarchical pricing structure from expensive boxes, medium priced pit seats, and cheaper seats in the gallery, managers calculated how many patrons a theater could seat and thus, if filled, what an evening's take would be. A house with generous box seating would bring in much more money than one of comparable size fitted with more gallery seating, for example. Taking specific accounts for Douglass' Chapel Street theater in New York and prorating the amount based on the size of our building, Odai Johnson has estimated that an evening's take in Williamsburg was more than £130, which was well above what we found in the Winston material to be average for a provincial theater at the end of the eighteenth century.43 Many, if not most English theaters ranged from £25 to £60. Johnson has shown that Douglass was well received in the South and Williamsburg in particular—so much so that he eventually got rid of gallery seating to add additional high-priced box seating. This meant that the upper level of the house had to be refitted to bring the quality of seating up to the standards of the boxes below.

Fig. 34. Seward's Theatre, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. Watercolor by Daniel Havell. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 3, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 34. Seward's Theatre, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. Watercolor by Daniel Havell. James Winston Theatric Tourist Notebook; HEW 13.4.2 vol. 2, page 3, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In terms of scale, the Williamsburg theater was bigger than the one in Richmond, North Yorkshire, and the auditorium nearly approached the size of the 1768 Edinburgh theater. It was virtually identical in size to the Bungay theater. All of these theaters had nicely appointed interiors. Smaller ones that might not have had boxes, or might simply contain pit-and-gallery seating appear to have had less architectural adornment, but the ones 22 that approached the Williamsburg theater in terms of nightly income seem to have been well fitted. In short, we would argue that given the amount of money that the Douglass Theatre probably generated, its interior must have been comparable to English provincial counterparts. Although we do not wish to make a case for over elaboration, we should not, on the other hand, think of our building as a colonial simulacrum of an English playhouse.

We have taken into consideration the fact that Williamsburg was Douglass's home base, the breadth of his playhouse-building experience before arriving, and the general knowledge locally about how a theater should look. Two small details bear testimony to a certain level of sophistication. The spikes found on this site contribute to the idea that our building had some level of refinement. They do appear in early nineteenth-century prints of London and seem to have been used in some of the better provincial theaters but were not universal. Sometimes spikes separated galleries from slips or side boxes and often sat on top of the partition dividing the orchestra pit from the seating in the pit. Interestingly, not only did the Douglass Theatre in Williamsburg have a spiked rail but the theater previous to it is known to have had one.44 We don't know if workmen constructed a ventilator for the Williamsburg theater, but it seems likely that one may have been added. The company played the town in the summer of 1770 and it seems likely that such a device was necessary to make such a season bearable. We do know that Douglass's Southwark theater in Philadelphia and his John Street theater in New York each had one before 1770. According to historian Richard Leacroft, ventilators began to appear in London theatres in the 1770s.45 Douglass did not invent the ventilator, but its presence in some of his American theaters does suggest a willingness to experiment and a degree of complexity in his designs. These small details indicate that Douglass's theaters were on the refined end of the provincial theater building spectrum.

History of the Douglass Theatre, 1760-1775

In an effort to evaluate the appropriateness of the variety of evidence, we tried to re-establish the process through which Douglass worked to have a theater constructed in Williamsburg in 1760. What were the historical circumstances that shaped this project? From his experience on stage in Britain and then working with a provincial company in the American colonies, Douglass had a thorough understanding of what a proper theater should look like, how it should be arranged, and how it should work as a money-making venture as well as a place to prepare and perform a variety of theatrical entertainments. No doubt, like many other managers in England and America, he had played in places that varied widely—from purpose-built theaters to temporary venues such as tavern long rooms, barns, and market houses.

From the Winston documents, it is evident that there were far fewer purpose-built structures in English county and market towns in the middle of the eighteenth century than at the end of the century. Many actors in second and third tier provincial companies spent much of their professional careers playing on temporary stages, rarely having the opportunity to perform in spaces specially created with raked stages, traps, orchestra pits, or even stage doors. They carried their scenery, wardrobe, and machinery with them as they journeyed their circuit of towns. The routine of taking down, moving, and setting up obviously took its wear on their equipment.46 What is remarkable about Douglass was his ability to establish a provincial circuit and erect so many permanent, purpose-built structures. However, his company also played secondary markets in places such as Norfolk, Petersburg, Baltimore, Chestertown, and other places, which did not always have theater buildings. In Fredericksburg they entertained audiences in a market house, while in Upper Marlborough, Maryland, they performed in a tobacco house, which was "well fitted for the purpose."47 His moveable scenery, props, and wardrobe obviously had to be flexible enough to suit his various 23 venues and his permanent buildings needed to be similarly arranged to accommodate the moveable possessions when the wagons were unloaded at each site.

Who designed and built the Douglass Theatre? Obviously the manager knew what he wanted, but how did he convey his ideas to the people responsible for building the theater? After all, the theater was a unique building in terms of its plan and many of its accouterments required specialized knowledge. Although Williamsburg residents had seen two earlier theaters, few had actually given much thought to their construction. Given the practice of building in Virginia in the late colonial period, the role of an architect as an individual capable of drafting plans, laying out specifications, and supervising the construction of a project was hardly known. Here and there were men capable of translating ideas onto paper, but most buildings erected in Virginia were devised on paper in the most cursorily manner—generally crude plans and elevations that set out the position of openings, partitions, and chimneys. These were working ideas and not blueprints for construction.

It is reasonable to believe that Douglass obtained the ear of a professional builder or contractor, perhaps a fellow mason who was willing to take on an extraordinary project at such short notice. Perhaps Douglass obtained the services of someone like Benjamin Powell, a man who had been trained in the woodworking trades and who had moved into the ranks of builders. He commanded a labor force and had access to ready money through securities to allow him to undertake large public building projects as well as private contracts for dwellings and other structures. Powell, or some other Williamsburg builder, would certainly have been part of the conversation with Douglass in the late summer of 1760 when the manager realized that his effort to build a theater in Williamsburg would bear fruit.

Did Douglass have a set of printed plans drafted for him by some unknown English architect or builder, which he carried with him to America and unrolled in each new town? It seems highly unlikely. What is more probable is that the manager had a firm grasp of what he needed from his lengthy stage experience, the construction of three earlier theaters, and his increasing knowledge of American audiences. He had a deep conceptual knowledge of how a theater worked—how it should be laid out to maximize seating capacity and how to get people into the various types of seats without sacrificing too much space to circulation, insure an orderly production by having ancillary rooms strategically placed alongside the stage, and the manner in which stage scenery was fashioned, operated, and stored. This information had to be conveyed to a builder in the clearest and simplest manner possible, especially since Douglass had not planned to stay in Williamsburg to oversee the work, but left after his agreements had been signed to rejoin his company on the road. Presumably, the design was the product of several animated conversations between Douglass and his contractor.

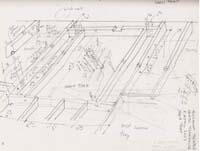

No doubt, the verbal description of what the manager wanted may have been accompanied by some basic sketches—a plan of the theater showing where the main doorway would be located, windows, stairs, corridors, and ancillary rooms. A rudimentary sectional drawing might have been produced to clarify the complex relationship of seats to stage. The sketches, if there were any, may not have been to scale or even done with any mark of draftsmanship for such was the case of many drawings of buildings that have survived from eighteenth-century Virginia.48 They were simply guideposts done by the client or builder for quick reference and agreement, especially for an unusual building type that was outside the standard building repertoire.

The most likely written instrument generated from this conversation would have been a set of specifications. These would have stated the basic obligations of the two parties noting, for example, who would supply what material, the quality of the materials to be used, and set a payment schedule and a timetable for completion. Douglass may have designated a Williamsburg resident, perhaps a fellow Mason, as his surrogate to monitor the progress of construction and provide further instruction to the builder during the process. The specifications would also describe the most salient features of the building—what it 24 would look like in the broadest terms—masonry foundations, wooden frame, and shingled roof. The exterior might be described by the type of cornice it was to have, the number of doors, and windows, or the paint colors. Much more detailed would be the interior specifications for the seats, stairs, plastering, roof framing, and finishes. Because of its unusual character, the specialized features such as traps, stage fittings, and machinery would be described in some detail so that the builder would understand exactly what was wanted. What was probably not included or only mentioned cursorily was the form of usual building features such as the wall and roof framing, the manner in which details were finished, the types of moldings to be used in a door, railing, or architrave. What was not spelled out was left to customary practices so that non-theatrical features would be built according to the local building conventions.49

One final source of design information may have derived from the previous theater. It is not clear how much if anything was left of the Murray-Kean theater, which had been constructed in the early 1750s when the town was filled with craftsmen working on a number of dwellings as well as the reconstruction of the Capitol. If some features of the old theater remained, then Douglass may have referred the builder to those forms as precedents. Perhaps, there were craftsmen in Williamsburg who may have been employed on the earlier structure and their expertise in fabricating specialized fittings may have been drawn upon for the design and construction of the new one. Certainly the memory of the building's layout would have informed their understanding of Douglass' instructions for the new edifice.

In the few months between his initial visit and his return with his company in the fall to play in the newly constructed theater, Douglass may have had some further communications with his builder by way of letters. He no doubt answered substantive questions that may have arisen once the project had begun and the reality of the construction process raised issues unforeseen in the initial discussions with the builder.

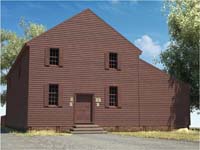

Fig. 35. Douglass Theater, view of the building site southeast of the Capitol, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Fig. 35. Douglass Theater, view of the building site southeast of the Capitol, Williamsburg, Virginia.

The contractor hired to build the theater had to work fast. Foremost, he had to finish or postpone any other projects in which he was engaged. He needed to hire or subcontract with specialists who could engage in bricklaying, joinery, plastering, glazing, and painting if he did not have men with those skills in his workforce of indentured servants, apprentices, and slaves. One of the first things he would have done was to develop a bill of scantling, which was a detailed list of the size, length, and number of framing members necessary for the construction of the theater, as well as an itemized list of other materials such as hardware and nails. And finally, the most pressing issue would be the procuring of materials at short notice. Williamsburg was not a large enough city to have a ready supply of pre-cut dimensioned timber, doors, windows, shingles, bricks and mortar on hand in local lumber yards and brickyards. Some of these may have been available, but perhaps not in the 25 quantities that were needed. As with most building projects, what was not on hand had to be gathered or manufactured immediately in a systematic manner to enable the schedule of work to proceed with as few disruptions as possible, which could easily be caused by an inadequate supply of materials or a skilled craftsmen not on the work site when he was needed.

Douglass probably foresaw that the Williamsburg theater would be a work in progress and that further refinements and changes would be made once it was made operational. Not everything had to be ready on opening night in October 1760, but he did need seats, a stage, and a roof. After all, as a traveling company used to venues of varying size and refinement, Douglass's actors were forced to improvise by habit. Much of their specialized equipment—the curtains, scenery, props, and costumes traveled with them. An unplastered ceiling may have had an impact on the acoustics, but they could still manage to put on their performances and thus begin to recoup the expenses of a new building.

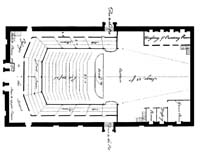

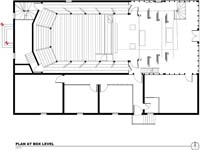

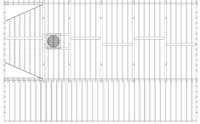

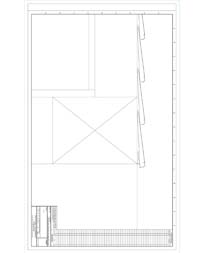

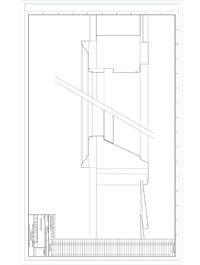

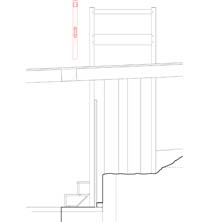

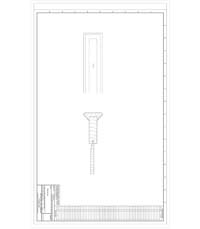

Fig. 36. Douglass Theater, archaeological plan, Williamsburg, Virginia. Drawn by Lisa Fischer.

Fig. 36. Douglass Theater, archaeological plan, Williamsburg, Virginia. Drawn by Lisa Fischer.

Sometimes, it took several seasons to finish a theater's décor or adjust the arrangement of ancillary rooms to improve the production. Audiences didn't seem to mind rough walls and unpainted spaces so long as what they saw on stage satisfied their expectations. For example, at the Georgian Theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire, the interior walls of the auditorium remained roughly finished for at least a generation, the stone and brickwork receiving only a coat of paint before they were eventually covered over by screens of canvas.50 Douglass went to great lengths to improve his theaters, not only to maximize profits by converting galleries into boxes, but to keep his company stocked with new scenery, which he commissioned on his periodic trips to London.51 For habitués of the theater, the great draw of each new season was the promise of new actors, new plays, and new sets. So, if on opening night in October, 1760, the smell of sawdust may have been strong and the paint barely dry, Douglass was less worried, knowing full well that there would be time for changes and improvements before the American Company came to town the next time.

Fig. 37. Douglass Theater, excavation of postholes, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Fig. 37. Douglass Theater, excavation of postholes, Williamsburg, Virginia.

So what did Douglass find when he returned to Williamsburg to open the new theater? His many subscribers who helped underwrite its construction had to be satisfied with their box seats and the full range of plays and entertainments. For the latter he could depend upon the talents of his seasoned 26 company, but the former was out of his control and entirely dependent upon the skills of the building contractor and his crew. What had this unknown individual along with the dozens of local workmen and laborers manage to accomplish in such a few short months? The fact that the construction was in an advanced enough state to open the season in conjunction with the meetings of the General Court and Houses of Burgesses—the public times that brought hundreds of people from across the province to the capital to transact the colony's business—is evident from the documents. Douglass had played his cards perfectly, lucky in the timing of his Williamsburg endeavor.

The Archaeological Evidence